In Conversation With: Henry Grover

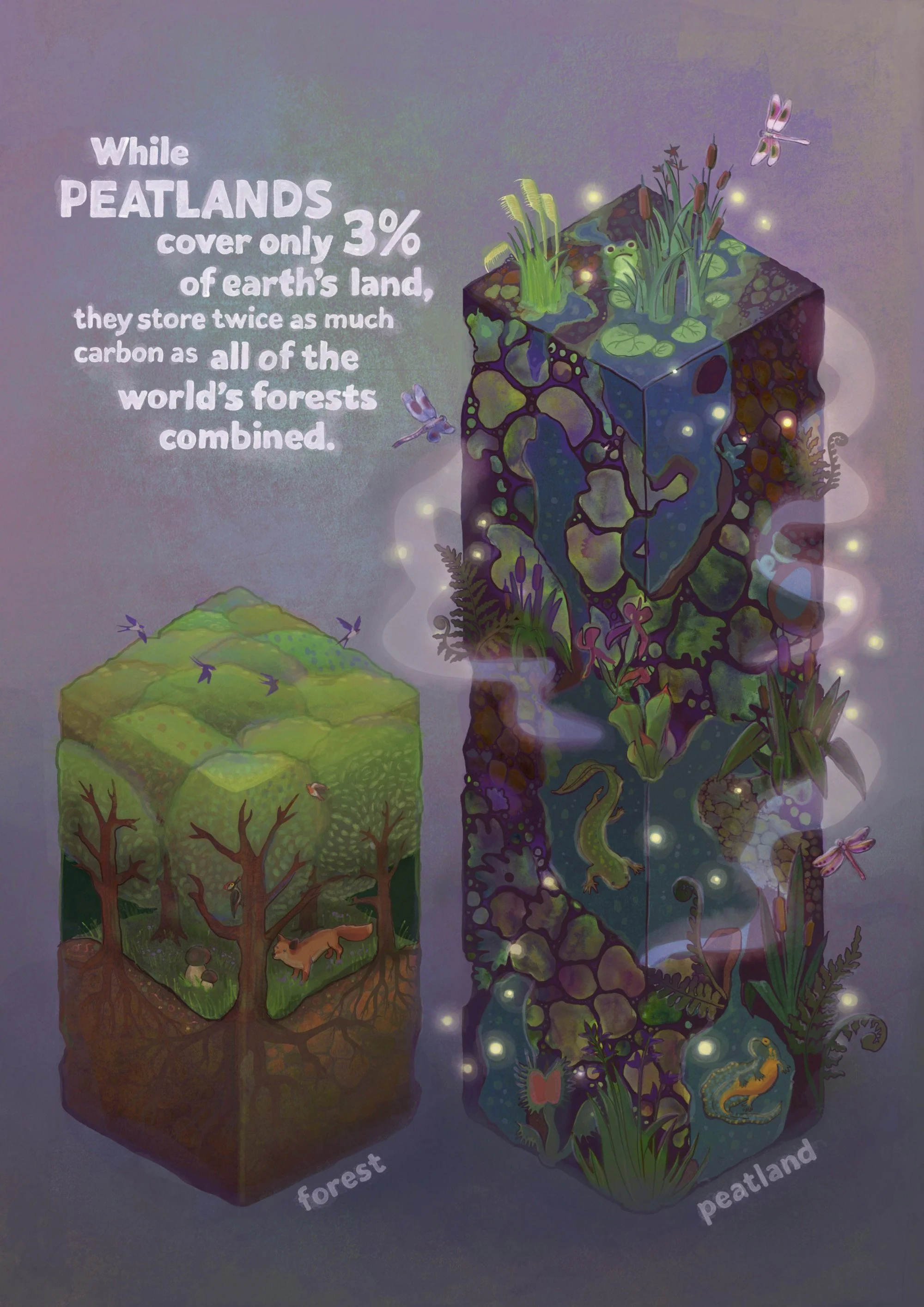

At Ponda, we have long admired the energy, creativity and determination behind RE-PEAT’s work. Their commitment to championing peatlands and the communities who depend on them - feels both urgent and deeply inspiring. RE-PEAT is a youth-led collective working across Europe, using creative advocacy to give peatlands the attention they deserve. Bringing together voices from art, science and activism, its members are united by a shared love for these vital ecosystems and a fierce commitment to protecting them.

Youth-led activism is essential in responding to the climate crisis, and it is always energising to connect with others who care about wetlands as deeply as we do. Over the coming months, we’ll be collaborating with RE-PEAT on a number of projects, but first, we wanted to introduce their brilliant team to the Ponda community. We’re delighted to sit down with them to explore how RE-PEAT began, the role of art in activism, and why peatlands deserve a much louder voice in the climate conversation.

To begin, could you share the story of how RE-PEAT first came to life? Where did the idea spark from, and how did it grow into what it is today? What are your best achievements in this time period?

Looking back now, it’s clear that September 2019 is a sort of BP and AP situation for a few of us: before peatlands and after peatlands. It was at this time that Bethany and Frankie were in Germany for a climate camp, which was set up to protest against a big chemical fertilizer company. They ended up spontaneously joining a peatland excursion and finding out about how vital peatlands are for the climate. On the bus ride home totally transfixed in this new mission, the name “re-peat” jokingly emerged. Since then, more and more people “re-peated” this moment of BP/AP, and so we formed a collective with many time-travelling multi-perspective starting points.

Over the course of the last five years together, we’ve learnt a lot more about peatlands. We have travelled across land and sea to visit them, listened to memories and built our own relationships with these landscapes. We’ve seen the importance of finding playful, metaphorical, collaborative, and imaginative ways of relating with peatlands and sharing their peculiar values. In return, the peatlands have guided us through explorations of grief, deep time, intergenerational thinking, migration, extraction, culture and more.

.png)

Since starting RE-PEAT, what is one of your favourite or most surprising things you’ve learned about peatlands?

People often think about peatlands as wet places, but when they are dry they become places that attract fire. Zombie fires can smolder underground for weeks, months and in some cases years… waiting in the shadows for the right moment to emerge into the light and reignite the world above. The idea of zombie fires is totally ominous, but also strangely magical in the way that they escape our view and our control. This is why peatlands, when kept wet and healthy, are such important mitigators of fire and drought. With their absorbent properties, they can also help prevent flooding. Peatlands are vital, intelligent regulators of landscapes, they are ecosystems we urgently need to care for and protect.

Wetlands and peatlands are often overlooked in climate discussions. Why do you think they remain so underrepresented, despite their huge ecological importance?

Wetlands and peatlands are often overlooked in climate discussions because of how they have been framed culturally and politically. They are frequently portrayed as wastelands, as “scary” or “empty” places. As landscapes to be drained rather than valued, making their ecological richness easy to ignore. Their degradation is also a form of slow violence: like the frog in hot water metaphor, the impacts unfold gradually and go unnoticed until it’s too late. For example in the Netherlands, soil subsidence from drained peatlands happens slowly, yet over time the land sinks by meters. Restoring peatlands is also slow. It requires landscape-wide agreement and collaboration between many actors, which is far harder to organise than restoration efforts focused on a single plot of land, such as forests.

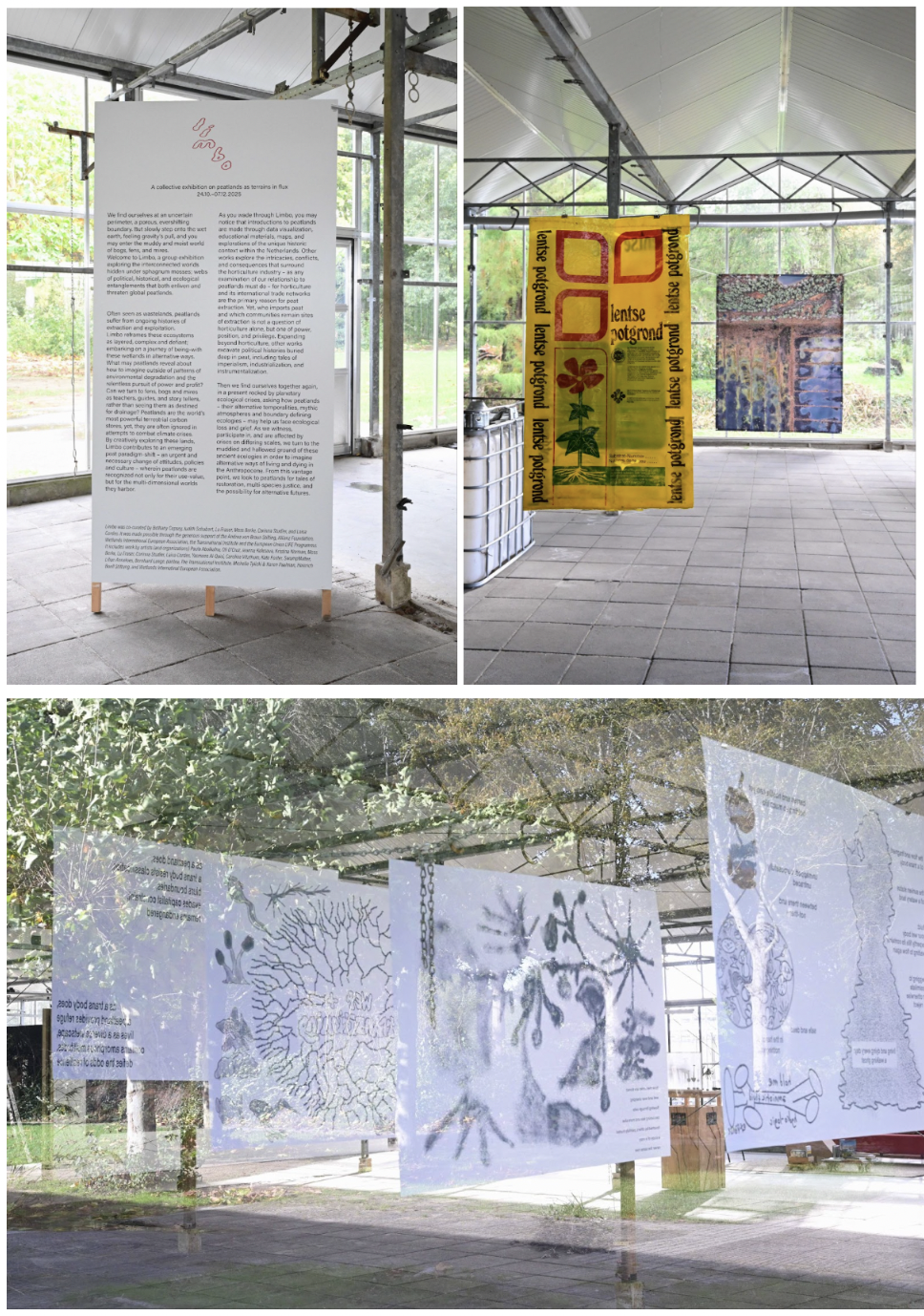

We delivered one of the largest peatland exhibitions to date, Limbo, created in collaboration with De Proef, a former horticultural school in the peat-rich province of Drenthe in the Netherlands. Inspired by the region’s long history of peat extraction, the exhibition brought together over 25 artists from around Europe, working across sound, data, video, and cartography to present peatlands as culturally complex landscapes rather than mere carbon stores. Alongside the exhibition, we hosted side-programming including lino-printing, artist talks, and a paludi dinner, pairing historical context with clear calls to action and significantly expanding the cultural and political visibility of peatland justice in the Netherlands.

The crowdfund supported the exhibition on a limited budget, ensuring fair artist compensation and enabling an interactive public programme, documentation, and a booklet that extends the work beyond the exhibition itself. Through over 200 pledges we reached just over €10,000! We are deeply grateful for the global network of supporters who made this possible.

Images from the Limbo exhibition taken by Caroline Vitzhum

Our latest short film 'Held by Nature, Shaped by Hands' was shot by the brilliant Henry Grover, who first approached us with a curiosity about Ponda and our supply chain. We had been searching for the best way to communicate what we do and who we are, without overcomplicating it, so this collaboration came at the perfect time.

What struck me most, and what Henry instinctively understood, is the sheer breadth of skill behind Ponda: engineers, agriculture specialists, designers. The people who make Ponda what it is are just as vital as the materials and processes themselves.

When people ask what Ponda does, I often struggle to offer a neat elevator pitch. I find myself jumping between regenerative agriculture, wetlands, biomaterials… because so many hands, minds, and disciplines feed into BioPuff. That’s why I was so excited to work with Henry to create a visual journey, one that captures the intimate, human-centred supply chain behind BioPuff. Each stage is crafted locally, just a few miles apart, by people working with care, skill, and intention. The process isn’t simply mechanical; it’s deeply human, grounded in collaboration and a sense of place.

In September, we took Henry to our team harvest at the RSPB Greylake site, and then back to our unit to see how Typha is transformed into BioPuff. Inspired by ASMR, the importance of every detail, and those deeply satisfying sounds, we are thrilled with the final result. I had envisioned a short, sharp film that could summarise what Ponda does, but Henry far exceeded that, capturing the essence of our work without needing a single word.

What first interested you about Ponda and made you want to reach out?

I have always been drawn to the intersection of innovation and tradition. I love the idea of new technology streamlining a process to be more sustainable without compromising on the quality of the end product. When I first discovered Ponda and BioPuff, it felt like a perfect case study for that balance. It’s rare to find a brand that is literally growing the future of textiles from the ground up. This excited me from a storytelling perspective; I didn't just want to show the product, but the 'how' and the 'who' - showcasing the intricate steps of the process and the passionate people driving the company forward.

How important was sound in helping you tell the story of the supply chain?

Sound is often the unsung hero of short-form film. In an era where so much content is consumed on mute via a phone screen, I wanted to create a soundcape that demands the viewer’s attention. I used sound as a transition to bridge the gap between the organic wetlands and the mechanical workshop. Without the layers of audio, you lose the tactile feel of the film. The audio makes it less of a highlights video and more of a film that immerses you in the process.

Was it challenging to capture each person’s role in just a matter of seconds?

It’s a constant balancing act. When you’re condensing a complex, multi-stage production line into 60 seconds, every frame has to earn its place. The challenge lies in juggling establishing shots, which give the viewer a sense of scale, with detailed shots that highlight the craftsmanship of Ponda. I find that much of today’s content cuts too aggressively, losing the moments to breathe. My goal was to maintain a high energy without sacrificing the viewer's ability to actually see the hands and faces behind the work.

.png)

From a technical perspective, what were the biggest challenges of shooting in such varied environments?

Aside from falling over in waders within five minutes of arriving at the wetlands, the real technical hurdle was maintaining visual cohesion across very different locations and lighting environments. I achieved this by shooting 90% of the film handheld, staying close to the action and tracking movements to create an organic flow.

I chose to shoot this on vintage Canon lenses from the 1980s. While they are slower to operate than modern glass, they provide a unique internal glow and a softer, more human aesthetic. This helped bridge the gap between the raw, natural environment of the plants and the industrial machinery of the workshop, making the entire journey feel like one continuous story.

How did you decide on the visual pacing, especially between organic and mechanical moments?

Pace is everything. If the film is constant high-speed movement, the viewer gets fatigued. I wanted to build in moments of stillness where a static wide shot allows the eye to rest and take in the environment. Ramping up the speed as the film went on was a way to mirror Ponda’s process. Starting slow in the wetlands and ramping up the speed as the machinery gets larger was a way to help the film move forward as Ponda’s process gets more intricate. The final shot, which circles back to the origin of the process, is intended to serve as a full-circle moment of reflection on the regenerative nature of their work.

.png)

What do you hope viewers take away from this film?

I hope it encourages people to pause and consider the biography of their clothing. Fast fashion has disconnected us from the environmental cost of our wardrobes. By tracing the supply chain back to the source, we can make more informed, intentional choices about quality and longevity.

Furthermore, in an era of AI and automation where there’s a lot of pessimism about the fading crafts, I want this film to offer a sense of optimism. I want viewers to see that there are still people deeply invested in the craft of making things better, more sustainably, and with genuine passion.

Henry’s website: https://www.henrygrover.uk/

Follow Henry: https://www.instagram.com/henrygroverfilm/

.png)

.png)